Postpartum depression is common among new mothers, according to current statistics. Understanding its risks and symptoms can help women receive the right treatment.

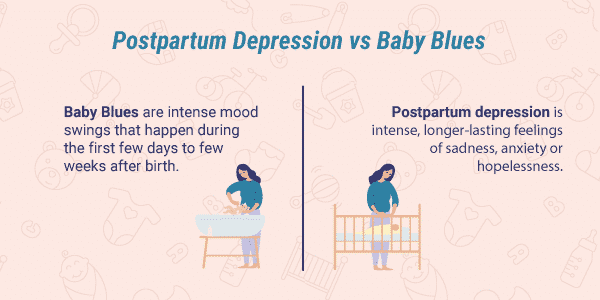

Having a baby is a life-changing event and brings about a new set of challenges. Even in a best-case scenario, giving birth is an emotional, stressful endeavor. Many women experience the baby blues, or intense mood swings that happen during the first few days to few weeks after birth. However, some will go on to developpostpartum depression, with more intense, longer-lasting feelings of sadness, anxiety or hopelessness.

Some stigma still surrounds postpartum depression. Many people are not aware of what it is and how serious it can be. An overview offacts about postpartum depressioncan help people learn about its signs, risk factors and widespread prevalence.

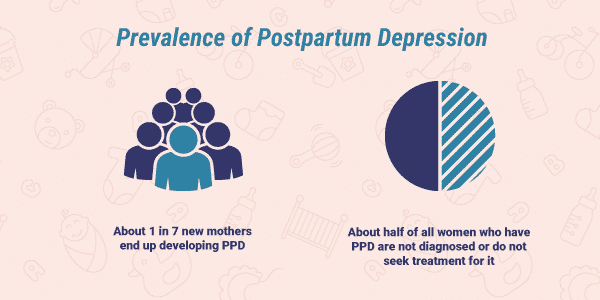

Prevalence of Postpartum Depression

About1 in 7new mothers end up developing postpartum depression.As many ashalfof all women who have postpartum depression are not diagnosed or do not seek treatment for it. Fortunately, theprevalence of postpartum depression in the United Stateshasdecreasedslightly over the past few decades.

Women aren’t the only ones affected by this condition. An estimated10.4%of new fathers experience symptoms of depression, more than twice the rate of other men.

Treatment Can Be Life Changing. Reach out today.

Whether you are struggling with addiction, mental health or both, our expert team is here to guide you every step of the way. Don’t wait— reach out today to take the first step toward taking control of your life.

Postpartum Depression vs. Baby Blues

Shortly after giving birth, women experience a sharp drop in the levels of the pregnancy hormones progesterone and estrogen. Around half of all new mothers experience mood swings related to these hormonal changes. Known as the “baby blues,” these mood swings often involve a broad spectrum of emotion, ranging from feelings of sadness and tearfulness to pleasure and joy. Typically, baby blues subside within the first few weeks after delivery.

Butpostpartum depression is different from the baby blues. The symptoms of postpartum depression last longer and significantly impact a woman’s ability to return to a normal life after giving birth.

Postpartum Depression Risk Factors

Any woman who has recently given birth is susceptible to developing postpartum depression. Certain psychological, obstetric, social and lifestylerisk factorscan make a woman more likely to develop the condition.

Psychological Factors:

- History ofdepressionoranxiety

- History of premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

- A negative attitude toward the baby

- Disappointment with the baby’s gender

- History of sexual abuse

Obstetric Factors:

- High-risk pregnancy

- Emergency cesarean section (C-section)

- Hospitalization during pregnancy

- Umbilical cord prolapse

- Premature birth

- Low birth weight

- Low hemoglobin

Social Factors:

- Lack of social support

- Domestic violence

Lifestyle Factors:

- Smoking during pregnancy

- Not getting enough sleep

- Low physical activity or exercise

- Poor diet

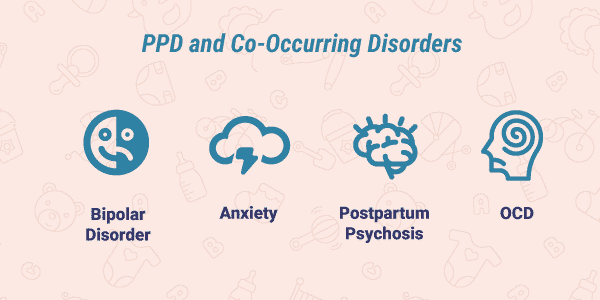

Rates of Postpartum Depression and Co-Occurring Disorders

Severalrelated conditionsfrequently co-occur with postpartum depression. They often have several symptoms in common.

- Postpartum Psychosis:Cases of postpartum psychosiscan occur along with postpartum depression. Therate of psychosisis relatively low, only affectingup to 3%of new mothers. However, diagnosing psychosis is especially important because it can significantly raise the risk of self-harm or infanticide.

- Bipolar Disorder:Between21–54%of women with postpartum depression also havebipolar disorder. The two conditions often occur together along with psychotic symptoms.

- Anxiety:Anxietyis a common symptom of postpartum depression. Along with postpartum depression, mothers frequently also experiencesymptoms ofanxiety disorders, affectingnearly two-thirdsof all women with postpartum depression.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder:New mothers have amuch higher riskthan other women for developingobsessive-compulsive disorder(OCD). Women who already have OCD are at risk for their symptoms getting worse after they give birth, especially if they also have postpartum depression.

Rates of Suicide or Infanticide

Intrusive, unwanted thoughts ofself-harmor harming their infants are surprisingly common among new mothers.Half of all new mothersreport having thoughts like these. Thankfully, these thoughts are not usually linked to an actual risk of causing harm.

Because they are rare, thesuicide rateand incidence ofinfanticideare hard to estimate in cases of postpartum depression. Around3%of new mothers with depression report having suicidal thoughts, though they don’t always act on them. Infanticide is often caused by postpartum psychosis.

Feelings of depression or anxiety can lead to suicidal thinking.If you or a loved one is experiencing suicidal thoughts or tendencies, call theNational Suicide Prevention Hotlineat1-800-273-8255.

Statistics on Postpartum Depression Treatment

Only half of all new mothers diagnosed with postpartum depression receive treatment for it. When leftuntreated, postpartum depressioncan become debilitating, significantly interfering with daily life. Mothers who receive effective treatment during their first month after giving birth have amuch betterprognosisthan if they go untreated.

Treatment for postpartum depressionoften includes antidepressant medication and counseling orcognitive behavioral therapy. TheFDA recently approved a new drugfor the treatment of postpartum depression. Called Brexanolone (brand name Zulresso), this is the first medication approved specifically for postpartum depression. The medication works by giving women a low dose of progesterone and estrogen to help make up for the sudden drop in these hormones following childbirth.

If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide or harming yourself or others, seek help immediately. Free, confidential help is available 24-7 at theNational Suicide Prevention Lifelineat 1-800-273-8255.

If you are affected by postpartum depression and a substance use disorder, considercontacting The Recovery Village. Representatives are available to answer your questions and recommend comprehensive treatment options.